Climate change is mobilizing more and more young people in Central Asia. Sooner or later, climate activists come up against the political mechanism created by humanity to solve this planetary problem – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Climate negotiations, which take place annually in the form of conferences of the parties to the UNFCCC, are becoming more complex each time: the language, the structure, and the conditions in which it all exists are becoming more complex.

We spoke with Alexandra Tulusoeva , a Buryat climate activist who has been living in Kazakhstan for several years, about how young people can find themselves in climate diplomacy. Alexandra works for the international youth network Care About Climate , is a member of the YOUNGO energy working group , was a member of the organizing committee of the Children and Youth Pavilion at COP29, and a delegate to the last three UN climate conferences: COP27 in 2022 in Egypt, COP28 in 2023 in the UAE, and COP29 in 2024 in Azerbaijan.

Aliya Vedelikh (AV): Tell us your story. How did you become interested in the climate issue, and how did you suddenly – or perhaps not suddenly – find yourself in climate negotiations?

Alexandra Tulusoeva (AT): I’ll start from afar. If we talk about interest in “ecology”, then it has always been with me.

I was born in Siberia, in a small village, I am an ethnic Buryat. Buryats are one of the indigenous peoples of Russia. Due to various cultural and religious reasons, the proximity of a unique natural object, Lake Baikal, we have a reverent attitude towards nature. Buryats have a close relationship with it.

But I didn’t think that I would build a career in “ecology” — I liked the topic of international relations, diplomacy. That’s why I studied to be an internationalist. After graduating from university with this education, I started working as a translator: I translated texts of different content.

Once I translated texts for a coal company. There were documents describing the indicators of sulfur dioxide emissions from coal combustion. I translated it all somehow automatically, that is, there, conventionally, emissions are two Chinese characters. Then I began to think about how these emissions affect us – even from the characters it was clear that this was something bad. Several years later, participating in climate negotiations, I will again see the importance of texts, but in a different context.

At first I was interested in the topic of energy and energy transition. Then step by step it all harmoniously moved into the topic of climate.

Before recording our interview, you mentioned different types of activism, including waste sorting. In my city, as a volunteer, I also started with such local actions.

But my academic background and subsequent experience have shown that many things are decided at the political level. Activism, even regularly, at the grassroots level is not enough if there is no access to the decision-making level. Because at the grassroots level, the problem does not receive a systemic solution and, in fact, is not solved. Such activity does not result in management measures or political reforms.

After working as a translator, I started looking for some opportunities in “ecology”. There were a lot of rejections, I even had a folder on my laptop called “Rejections”. Then, as it turned out later, everything worked out very well, and rejections sometimes happen so that you end up in another, more suitable place. My big advocacy began with an organization called Youth and Environment Europe . It is a large network uniting youth environmental NGOs in Europe. There I got into a leadership program, I was chosen as a coordinator for sustainable energy.

It was 2022, and Europe was in the midst of an energy crisis due to the reduction in Russian gas supplies. In this network, my colleagues and I were involved in campaigns and fundraising. For example, we launched a campaign for young people from countries particularly vulnerable to the energy crisis. We determined vulnerability by how much the reduction in gas supplies would affect price growth. We prepared various toolkits on how young women and men could influence the energy and environmental policies of their countries.

With the same organization I got to my first COP (from the English COP, the Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, or the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – editor’s note ), it was COP27 in Egypt. It was called the African COP, because, on the one hand, it was in Sharm el-Sheikh, on the other hand, there was a lot of focus on the topic of loss and damage, or losses and damage from the effects of climate change. This topic impressed me greatly.

I was with Youth and Environment Europe for a little over a year. Now I am with another organization, Care About Climate . Its geography is wider – it works at the international level, and it also consists entirely of activists who have joined us from different parts of the world. This has its advantages, since our international team never stops working, but it also has its challenges: when we have team calls, for some it may be midnight, for others it may be seven in the morning – it is not so easy to gather all the time zones together.

AV: Tell us what you are currently doing at Care About Climate.

AT: The main focus of the organization is to give young people tools for effective engagement in climate negotiations. I am involved in several projects: the main one is a course on climate political advocacy at the international level, and we also have a tracker for equality of nationally determined contributions, the NDC Equity Tracker.

The climate advocacy course is more than 10 hours of material: from the history of the adoption of the Framework Convention on Climate Change to practical advice on how to take care of your mental health during the COP. We translate the content into six UN languages and adapt it, and I am the one translating it into Russian.

We update it every year, depending on the decisions made at the next conference of the parties, or other circumstances, so that the course remains relevant.

The second project is the NDC Equity Tracker , which tracks the equity of countries’ NDCs (nationally determined contributions; this refers to a country’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as part of a global effort – editor’s note ). There, we track the extent to which countries’ commitments take into account youth and gender. At COP29, we launched another initiative called the NDC Youth Clause . It calls on – but does not require – countries to include indicators on youth and “gender” in their NDCs.

AV: I would like to ask about options for influencing the negotiations. As far as I understand, activist groups between COPs monitor progress on their topics, then formulate messages with which they put pressure on certain countries at the next COP. That is, activists carry out work related to the negotiations: between COPs – through involvement in working groups and communication campaigns, before the COPs – through pressure campaigns, at the COPs themselves – directly through observation, speeches and actions. Are there other options for influencing the negotiation processes?

Why am I asking this? Because at COP29, and this was my first COP, I noticed that delegates from Central Asia were hanging out mostly in pavilions: they come from behind the pavilion, do something for 2-3 days in the pavilion and leave. It seemed to me that pavilions are a story that is not very connected with the negotiations themselves. Or am I wrong and it is also possible to somehow influence the negotiations through pavilions?

AT: Journalists increasingly compare climate COPs with the World Economic Forum in Davos, with a large fair – because in addition to negotiators, everyone comes. They come to conclude trade deals in pavilions that are, in fact, not part of the negotiations.

If the results of these deals have a positive impact on the political ambitions or economic interests of the country, I am certainly not against it… But it is true that such a number of pavilions, such attention to them, such a huge number of side events, are really very distracting.

I don’t think professional negotiators, immersed in their work, even find time to visit the pavilion area. At COP29, I spoke with the Mongolian delegation: they literally did not leave the plenary sessions.

As for the impact on the negotiation process. All procedures at climate COPs are subject to the general UN procedures, and they are quite conservative. Starting with the most basic rule of consensus, when a decision is made only by consensus of the parties, and not by a majority vote. This is a fairly conservative measure that slows down progress, but it also has its advantages. What do I want to say? The entire negotiation process within the UNFCCC is conservative and standardized, and it seems to me that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to interfere in it in some way to directly influence the negotiations.

Now the presidency, that is, the chairmanship of the country hosting the conference, has a greater influence on the negotiations. For example, the final decision at COP29 was made by “forced consensus” (without hearing the countries that wanted to speak on it — editor’s note ). As far as I know, this also happened in Mexico (COP16 in Cancun in 2010 — editor’s note ).

In terms of civil society’s influence on negotiations: I know that there are attempts to “catch” negotiators, literally push them against the wall and convey your position. We also had such a strategy at Youngo with an energy track: we literally stood near the doors of rooms and “caught” some high-ranking officials – we recognized them by face, had to google their names, remember what they look like. We grabbed the Norwegian minister by the hand and conveyed our message to him. And then it depends on the negotiator: to what extent he or she will listen to you, how important the topic of youth or youth initiatives are for them.

Someone is really listening: we have thrown them this seed, then they will probably encounter something like this somewhere else, the seed will sprout and this will give a positive result. That is, activists need to convey their messages systematically and press with quantity. But it is precisely with regard to such direct influence from civil society on negotiations that I am, unfortunately, quite pessimistic.

Perhaps, when there are some super sensitive and important topics, as was the case, for example, with funding for COP29 in Baku. Civil society united into one living organism, which demanded increased ambitions on the issue of funding.

I participated in this too. On November 16, at the Global Day of Action at COP29, we held big protests: everyone gathered with different slogans, first in the plenary hall, then in the corridors where the negotiators were passing. They saw us and the despair in our eyes, read our banners, some even took pictures. It works on some, it doesn’t work on others at all. I even saw an opinion that such things should be banned, because they distract negotiators from the essence of the negotiations.

It seems to me that such actions at the negotiations complement the general context from which the negotiators are pushing off. By the way, the UNFCCC is one of the few such UN platforms where protests are allowed and where, including through them, the voice of developing and least developed countries can be heard.

AV: A few weeks ago we wrote about the experience of Egypt : how this country supplements its official delegations with youth negotiators who, if they do not speak at the negotiations themselves, at least monitor the tracks.

Do you think this experience is applicable in Central Asian countries or other post-Soviet countries? Can our governments, which currently lack the internal capacity to monitor all the tracks and interests of their countries in negotiations, recruit young negotiators, develop their potential and use this potential? Is this option suitable for us at all?

AT: Unfortunately, I have not heard about this program in Egypt, but I know that other countries also practice this. Sweden and Denmark actively include young people in their delegations. As far as I know, Italy and Mexico are also working on this: they have separate quotas for young people in their delegations.

How would this work in Central Asian countries? I can only share my opinion as an outside observer, since I was not born and raised in the region. Here, it seems to me, you need to understand why exactly you want to build capacity and raise a new generation of negotiators. To convey the voice of youth or to represent the interests of the country? The latter sounds more realistic, because the demands of youth sometimes diverge from state policy.

It is clear that young people have more ambitious requirements, we set a higher bar, which is difficult to achieve, but it is possible to strive for. But in any case, such potential needs to be built up: trained, given the opportunity for practice to future negotiators.

If we look to the future, there is climate change, and it is clear that with each passing year, with each new generation, it will be more and more difficult to slow it down. How to adapt? How will finances be distributed? What new challenges will there be in 30 years? Those who are currently studying in schools and universities will have to deal with all of this.

We need to prepare young people now to defend their country’s interests in climate negotiations. And there are already successful examples in the region that we can learn from – for example, Kyrgyzstan with its mountain agenda.

These could be some kind of mentoring programs from current negotiators. So that young people understand the priorities of their country, have experience of participating in such discussions. There are many active young people in Central Asia. I look at Alimkhan ( Alimkhan Abulkhan is the head of the student organization Climate for Us , an environmental student at Almaty University and a delegate to COP29 – editor’s note ), who is literally just over 20 years old and who does so much… In terms of knowledge of languages, in terms of desire and skills – it seems to me that your young activists have great potential. We need to create conditions for its development.

AV: Next year, all countries should update their NDCs, increase the ambition of their reduction commitments. I don’t quite believe that some countries in our region will actually increase the ambition of their NDCs, but we’ll see what happens.

Do you have examples of effective youth influence on the ONUVs of your countries? Or at least examples of how comments from youth are taken seriously in this process?

You said that one of your projects is the NDC tracker on youth and children inclusion. Among the countries that were assessed in this tracker, were there any that took your assessment into account and started to include the interests of children and youth in their climate commitments?

AT: At COP29, we launched an initiative within this tracker project: a call for countries to include youth provisions in their NDCs. Any government can make such voluntary commitments. In Baku, the UK did this, there was an official ceremony where the UK announced that it had joined the Care About Climate initiative and made such commitments. Now we are working on getting other countries involved. We may do this in the Central Asian region as well.

If you mean the influence of youth on reducing emissions, then it is more difficult to track to what extent a particular country relied on the opinion of youth when adopting its NDCs…

Climate commitments of Central Asian countries.

What is NDC 3.0? Read >>>

AV: Either on emissions or on the adaptation component in the NDC… I want to explain why I am asking about this. Because in Central Asia, young people do not read the NDC and, in general, do not engage in political advocacy. In climate and eco-activism, it turned out that our older colleagues were engaged in political advocacy, reached the level of ministries and so on, but the younger generation… I got the impression that many of those who went to Baku for the negotiations did not open the NDC of their country.

In Kazakhstan, when the draft of the updated NDC was submitted for public discussion… And not only the NDC – the Strategy for Achieving Carbon Neutrality… Very few young activists participated in their discussion. They explain this by saying that, like, they won’t listen to us anyway. But as long as we don’t participate in this, naturally, they won’t listen to us.

How can we get young people interested in NDCs? So that climate activism is also political advocacy, and not some personal example of pseudo-climate activism?

AT: Political advocacy among young people is difficult in principle everywhere in developing countries, not just in Central Asia. This type of activism scares many people because it involves the word “politics.” Going out to protest, even environmental ones, is not always safe…

AV: I am not talking about protests, but about expressing one’s opinion at the decision-making level. For example, in Kazakhstan there is “Open NPA” – a portal where draft normative legal acts are submitted and where the public is given a certain time, usually two weeks, to comment on the draft. In our country, people generally demand and want all this, but when it appears as an opportunity, they do not participate in it, and especially young activists – this is the group that ignores this instrument.

AT: I understand your concerns, but I don’t think I have the right to criticize the youth of Central Asia, since I didn’t grow up here myself.

AV: Do you have any successful examples of youth influence on ONUV?

AT: Specifically on ONU, you probably don’t….

AV: Or in general on the climate policy of an individual country?

AT: Since I interned at a European NGO, I have such examples from Europe. But this does not mean that European activists are doing well in political advocacy, while we are doing badly. There, active youth really do have a high level of advocacy. I learned a lot from guys and girls who were five years younger than me.

They monitor everything: they read all new bills, all the documentation related to them, discuss the texts together. They find weak points and write comments on them. They seek access to ministers, including through informal channels. They initiate meetings with decision-makers, where they put forward their demands. Thanks to the fact that all this works there and the ministers listen, the youth there is so active. If a large group of young people comes to a minister’s meeting, you can’t just ignore them.

I don’t know how it works in Central Asia. If, say, you ask the minister for a meeting, will you as an activist group be heard? This, of course, is taking into account that you are 100% prepared and have all the justifications in hand. But we need to understand why Central Asian youth have such a prejudice.

AV: I think that these are echoes of the same idea that was hammered into Russians and got us hooked. The idea that politics is none of our business, that it is better not to get involved in it, that politicians should deal with politics, and so on. Plus, in the post-Soviet space as a whole, the power of the “piece of paper” remains, without which you are nobody.

And our activists rarely bring their comments to government agencies in paper form. Therefore, everything remains in words, and over time, they are forgotten. I think that it is generally beneficial for ministries when the public addresses them officially, in writing – this reinforces the relevance of what the ministries do. And for activists, this is a useful practice, which, at a minimum, increases their status.

AT: I would also like to note that being a climate activist at a young age and being able to understand everything and approach ministers is also about privileges. Let me explain. When I look at my colleagues from Europe, I understand that many of them are from wealthy families, not the first or even the second generation of university graduates, their parents are involved in political activism or are concerned about “ecology”. That is, all this does not come out of thin air and not because the person is good and talented, but from the entire context: the socio-economic background, the political context, the history of the country.

And if you are a young person in a poor country, even in the same Global North, you have to strain yourself not to lose your scholarship, or work part-time because you have nothing to pay for your studies or housing, get to the university every day through traffic jams and then return home, help your parents… In such conditions, keeping track of the bill is quite difficult.

AV: What are your plans for the future?

AT: I am still interested in the topic of climate diplomacy, I see myself in it in the future. But paradoxically, I have no experience as a negotiator. Because I participated in negotiations in absolutely different ways, but not as a negotiator.

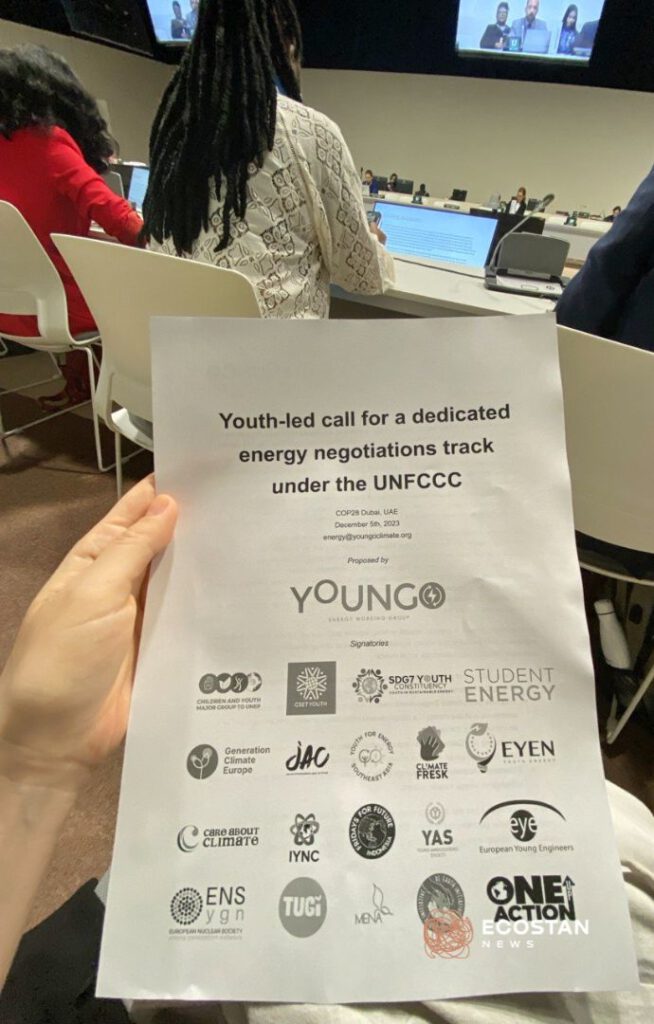

For example, in Youngo, the youth organization of the UNFCCC, I am a member of the energy working group. With it, we promote the need for a separate track on energy in the UN climate negotiations. Because there is, for example, a track on damage and loss, there is a track on adaptation, and the topic of energy, which seems to us to be the most important, is spread across different tracks: a just transition, a working program on mitigation or Global Stocktake (Global stocktake of climate actions – editor’s note), together with formulations on the gradual abandonment of fossil fuels. But there is no separate energy track.

Because of this, it is quite difficult to take on obligations on energy, to take any measures, to put pressure on your countries… That is why we at Youngo are currently conducting an advocacy campaign to include such a track. However, the UNFCCC does not look at this very well yet – because for them it is a lot of work and a lot of resources.

I also participated in the negotiations as an observer from various civil society groups. In some places I made reports on the progress of the negotiations, in others I simply observed – I came to the negotiations and followed their dynamics.

At one of the side events (parallel events at UN climate conferences — editor’s note) at COP28 in Dubai, there was a very interesting question: if you want to be a negotiator for your country, do you have to share its position in the negotiations 100%? At the moment, my vision of what is needed differs from how my country behaves in the negotiations. That’s why I have not yet participated in the negotiations directly.

I recently learned of such an opportunity: some least developed countries and island developing states hire independent consultants from various NGOs as negotiators. Many of these countries do not have their own resources to ensure their participation and advance their position in the negotiations. For example, to organize a trip for all their negotiators to Brazil next year, where COP30 will be held. This is beyond their resources and, unfortunately, the capabilities of their official delegations.

Consultants volunteer to help: somewhere on a pro bono basis, somewhere for the sake of the reputation of NGOs, in general — pro bono. They defend the rights of the least developed economies in climate negotiations. This to some extent balances the negotiating capabilities of developed and developing countries. For example, the interests of the United States are represented by lawyers who graduated from, say, Columbia University. And it is somehow not quite right when the delegation of island states is represented by a couple of people and they cannot attend and monitor negotiations on all tracks. Being a consultant in this case is an opportunity to fill the gap in the potential of the least developed countries.

This is probably something I would like to do in the near future. But for now, it is a difficult moral dilemma for me: to what extent do I have the right to represent the interests of a country with which I have absolutely nothing in common in terms of cultural background? At COP29, I met with a negotiator from the UK who represents Angola. Because it is close to her values.

Fiction “Ministry of the Future” and non-fiction “On Behalf of My Delegation” – recommendations from climate activist Alexandra Tulusoeva:

I would like to recommend to those interested in climate diplomacy and climate activism the book “The Ministry for the Future” by Kim Stanley Robinson. This is a fiction about how humanity resorts to completely different solutions to prevent a planetary catastrophe. But it does so when it is already too late to change anything and it is in full swing.

The action begins in India, where 20 million people die from a savage heat wave. This tragedy leads to the radicalization of climate activists – they decide to take matters into their own hands and do it in extreme ways: blowing up coal mines, threatening planes…

In parallel, there is a narrative about the work of the fictional Ministry of the Future, which operates under the auspices of the UN. It is engaged in protecting the rights of unborn generations. The decision to create it was allegedly made at COP29, it began working just a few months before the tragedy in India.

Why did it hook me? When you start thinking about what these climate summits are for, how to influence progress, you dig deeper and deeper… You start thinking about the political and economic structure of the world. This book really helps you see all these aspects.

Rather than offering simple solutions, it shows how complex and multifaceted the climate crisis is. The author combines fiction with scientific accuracy, touching on topics that are already being debated in academic and political circles. For example, could geoengineering be a real solution? Or how can the global financial system be changed so that it supports sustainable development rather than exacerbating the crisis? Another recommendation is the IISD guide “On Behalf of My Delegation,” which examines the problem of climate change itself, the history of climate negotiations, and the rules and procedures of the UN. This “survival guide” also offers a lot of practical advice for aspiring negotiators.