Island of Infection

How the USSR tested biological weapons on animals and people in the middle of the Aral Sea

In the middle of a desert steppe covered with brown thorns and surrounded by the sea, there is a testing area divided into segments. Inside each segment, monkeys, guinea pigs, dogs, rabbits, horses and sheep are tied to pegs in cages.

A dull bang. A metal ball soars into the sky. It spins, and then explodes from within. A thick mustard-colored cloud descends on the animals, and they, as if sensing death, begin to scream and rush about the cages. The monkeys, closing their eyes, hide their mouths and noses with their paws, try to save themselves. But in vain.

At the other end of the island, a group of people in anti-plague suits stand watching the experiment. They record the animals’ reactions. In a few days, the results of the carcass tests will show that the test was successful: the new Soviet bioweapon is deadly and ready to be unleashed on the enemy.

“Kedr.media” and “Free Space” tell about Vozrozhdeniya Island, which as a result of the arms race between the USSR and the USA turned into one of the most dangerous places on the planet. The degree of contamination of its territory with anthrax spores and other infections, from which Soviet scientists and military tried to make weapons, is still classified, but due to the drying up of the Aral Sea, the island again threatens people.

Hello, weapons!

In 1946, the Cold War began between the USSR and the USA, one of the elements of which was the arms race. For more than 40 years (from 1947 to 1990), the states tried to surpass each other in military power. The main goal of the race was to develop the most advanced weapons of mass destruction, including biological ones.

Aralsk-7. Photo: MASTAK / panoramio.com

Both countries had a strategy for waging bacteriological warfare. The Soviet doctrine assumed that the combat agent tularemia ( an acute infectious disease with fever, damage to the lymph nodes, eyes and lungs . – Ed. ) could be used if the enemy’s manpower needed to be temporarily incapacitated: with this disease, only 1% of those infected die, the rest are paralyzed. And the use of combat plague, which was dubbed the “weapon of despair”, was supposed in the event of an active enemy offensive: its action is characterized by a short incubation period, transience, complete insensitivity to antibiotics and 100% mortality.

The Soviet Union began developing bioweapons in earnest in 1946. The secret program involved more than 50,000 specialists. They developed, produced, and tested hundreds of tons of deadly toxins and biological agents throughout the USSR (there were 52 sites related to the production and testing of bioweapons on its territory).

The main location for testing Soviet bacteriological weapons was Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea. Here, for 40 years, clouds of smallpox, anthrax, plague, typhus, brucellosis and other diseases hovered, penetrating the sandy soil with rain and accumulating in it.

Thousands of experimental animals died on the island, and cases of infection with combat diseases were recorded among the residents of the Aral Sea region, who did not know what kind of danger was neighboring them.

Even 31 years after the closure of the biochemical test site, it is impossible to find reliable data on the details of its work and the ecological and epidemiological state of Vozrozhdeniya Island – they are still classified.

Salt and Tears

After the Soviet government diverted the waters of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, which feed the Aral Sea, to irrigate cotton fields in the 1960s, the Aral began to dry up. In 1985–1986, the sea level dropped from 53 to 41 meters — the Aral split into two bodies of water: the Small Aral (in Kazakhstan) and the Big Aral (in Uzbekistan). By 2002, the sea level had dropped another 10 meters. Ships ended up in the sand, and local residents found themselves at the epicenter of a large-scale environmental disaster. In total, from 1960 to 2009, the area of the Aral Sea decreased by 10 times (from 67,499 km² to 6,700 km²).

As a result of the anthropogenic crisis, hundreds of Aral islands became part of the Aralkum desert that formed in place of the sea. Aralkum is 38,000 km² of salty sand, soaked in toxic pesticides that were washed off from irrigated fields.

After dust and salt storms began to spread sand from Aralkum mixed with salt and fertilizer waste for 500 km around, abnormal infant mortality and an increase in cancer cases began to be noted in the Aral Sea region .

One of the Aral islands that has merged with the land is Vozrozhdeniya Island, where the largest biochemical testing site, Barkhan, operated for 40 years (from 1952 to 1992). The work of the testing site turned Vozrozhdeniya Island into one of the most dangerous places on the planet.

Infection zone

Vozrozhdeniya Island was formed in the late 16th – early 17th centuries as a result of the decline of the Aral Sea*. It was discovered in 1848 by Russian naval figure Alexei Butakov. A lively fishing village soon appeared on the island. Herds of saiga antelope grazed here, and the local bays were full of waterfowl and fish.

In 1948, exactly one hundred years later, normal life ended. Local residents were forced to leave the island after the Soviet leadership decided to create a military testing ground. According to Soviet officials, the hot climate of Vozrozhdeniya Island met the safety requirements for testing biological weapons: bacteria and viruses are very sensitive to sunlight – ultraviolet rays are harmful to them. And the isolated location of the island, surrounded by the sea, was supposed to be a reliable shelter for the testing ground from foreign intelligence. However, in 1962, American satellite intelligence still learned of the existence of a testing ground in the middle of the Aral Sea, after which it began to regularly monitor military activity there.

By 1952, Vozrozhdeniya Island had acquired an airfield, a testing site, scientific laboratories, and a small military town called Kantubek (Aralsk-7). The secret island was under constant guard. On the water, the territory was patrolled by military boats, on land, patrol cars guarded it, and the testing ground and laboratory complex were surrounded by barbed wire.

On the island, in addition to the test site employees and their families, there were at least 800 servicemen who serviced the secret facility. The conscripts watched the explosions of bombs filled with dangerous infectious agents, removed the carcasses of infected animals from the sites, and tried not to talk about what was happening, even to each other.

A former signalman at the testing ground spoke about his service on the island:

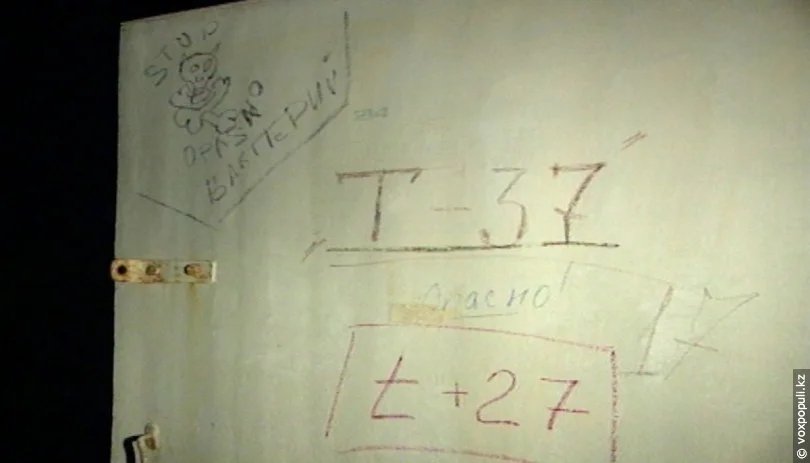

The sign on the door reads: “Danger! T -37, t +27.” A temperature of minus 37 degrees Celsius is optimal for storing strains of bubonic plague, and plus 27 is optimal for storing spores of anthrax or anthrax. The graffiti in the upper left corner is modern, from stalkers. The dungeon of the main laboratory complex of the Aralsk-7 testing ground. Photo: voxpopull.kz

“You can guess that we will serve in a difficult place immediately upon arrival in Aralsk. The special officer conducted a conversation, they warned us that the facility was secret. They asked our parents to write not to come. <…> Not everyone was sent there. They probably looked at biographies, where they were from. Muscovites, Urals, Perm served in the military, I remember…

<…> There were a lot of chemists and doctors among the officers. But it became clear later why. <…> In principle, everyone understood that some kind of weapons were being tested.

But I believe that none of the rank and file imagined that right here on the island, bacteriological bombs with bubonic plague and other particularly dangerous infections were being detonated.

<…> This [testing at the proving ground] was never discussed among the soldiers. The special department worked precisely. Everyone was afraid, apparently. <…> Since I was a radio operator, I knew: large batches of monkeys were regularly brought to the island, apparently directly from Africa. They also brought bananas and seeds, obviously for their food.

A little later, when the massive reconstruction of the third building, a huge three-story building, began, I had to work there. I saw rows of cages, empty at the time. I knew that at the entrance to the testing area there were three hermetically sealed cabins for decontamination. They only went in there in suits. <…> There were no major emergencies. Just shortly before our arrival, I heard that the constant wind changed and blew towards the military town from the direction of the testing ground. So the entire town was immediately evacuated.

And health problems – how could they be otherwise? Constant “furunculoses” – that was our everyday life. And a year after my arrival there was a terrible hepatitis epidemic. Of the eight hundred soldiers, five or six hundred were lying in the hospital. Many were infected two or three times. Naturally, they were no longer healthy after that.

<…> I think I was saved by the fact that I was a radio operator and had no direct contact with the source of infection. But what I took away from Vozrozhdeniya Island was an absolute intolerance to chlorine (they just didn’t force us to swim in it) and a weakened immune system.”

The main building of the site In the now abandoned PNIL-52 (field research laboratory) for testing biological weapons. Still from ZweZet videos

The Barkhan testing ground occupied the southern part of Vozrozhdeniya Island. The weapon was tested on experimental dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs, rats, horses, sheep and monkeys. According to Soviet military biologist Kanatzhan Alibekov, who worked on the creation of bioweapons, monkeys were best suited for testing, since their respiratory organs are very similar to those of humans.

Alibekov, who emigrated to the United States after the collapse of the USSR, later recalled the tests on the Aral Sea:

“Dozens of baboons are tied to pegs, and high above them a shell explodes, leaving behind a brownish cloud.

Animals know nothing about biological weapons, but, as if sensing death, they instinctively cover their noses and mouths with their paws.”

Alibekov admitted that years later he “well remembers the eyes of the experimental animals driven to their death.”

— I was in the “zone” several times. Soldiers never went there. But I had to. I saw sick monkeys sitting in cages. One of them was crying, another was trying to move, the third was lying half-dead. And one grabbed the tube of my gas mask, asking for help, — said former serviceman of the training ground Sergei Telenkov.

After the tests, scientists studied the bodies of infected animals, then burned the dead carcasses and buried them in special burial grounds. After each test, the testing ground was thoroughly disinfected to prevent virus leaks. But the viruses from the island still found their way to unsuspecting local residents…

As test subjects

In 1971, while sailing on the research vessel Lev Berg, which, having lost its course, fell into an aerosol cloud of smallpox near the island, a female scientist fell ill. After her return to Aralsk, an outbreak of the infection occurred in the city. As a result, nine people were infected with smallpox. Three of them died. Among the dead was the researcher’s younger brother; she herself survived. The Soviet authorities then managed to hide the outbreak from the world – officials did not report it to the World Health Organization.

Pyotr Burgasov, who served as Deputy Minister of Health of the USSR at the time, recalled many years later :

“On Vozrozhdeniya Island in the Aral Sea, the strongest smallpox formula was being tested. Suddenly, I am informed that there are strange deaths in Aralsk.

What turned out was this: a research ship of the Aral Shipping Company approached the island at a distance of 15 km (it was forbidden to approach closer than 40 km), a lab assistant went out on deck twice a day and took plankton samples. The smallpox pathogen – and only 400 grams were blown up on the island at that time – “got” her, she became infected, and upon returning home to Aralsk, she infected several more people, including children.

Having guessed what was going on, I called the Chief of the General Staff and asked him to prohibit the Alma-Ata-Moscow trains from stopping in Aralsk. Thus, an epidemic was prevented throughout the country. I called Andropov, then head of the KGB, and reported that an exclusive smallpox recipe had been obtained on Vozrozhdeniya Island. He ordered that not a word more be said about it. That’s what a real bacterium weapon is!

The minimum range is 15 km. One can imagine what would happen if 100–200 people were in the lab assistant’s place.”

A similar story of a person being infected with a dangerous infection happened in 1972, when fishermen who had gone missing earlier were found dead in a boat drifting near the island. The cause of death was presumably the plague.

Former serviceman of the range Leonid Basenko told a story that he witnessed: near the island of Vozrozhdeniya, local fishermen caught a fox, and three days later – died of pneumonic plague. The animal turned out to be infected.

It is also known that periodically, conscripts serving on the island developed contact dermatitis – their skin became covered in ulcers. However, no one told the soldiers about the bacteriological danger: all data on the tests conducted in the USSR were classified. Even as of 2022, it is unknown how many people suffered from toxic fallout, soil and water contamination, and the spread of combat agents of dangerous diseases.

The island’s nature also fell victim to Soviet experiments. But how exactly the bioweapons tests affected the environment of the Aral Sea region is still unknown. Serviceman Leonid Basenko recalled that in one of the locations on the island, with an area of about a square kilometer, “there was nothing: not a tree, not a single rodent hole – just bare earth.”

In the 1970s, the island’s inhabitants often pulled dead fish out of the sea. And among the rodents that inhabited the area north of the test site, according to biologist Kanatzhan Alibekov, there was a high incidence of plague in the 1970s and 80s. In 1988, 50,000 saigas died almost instantly in the steppe near the island. What exactly caused their death remains unknown: scientists to this day cannot establish for sure whether the mass death of animals was connected with the work of the test site – all important documents about the tests on the island remain classified and are stored in the Russian Ministry of Defense.

In the same year of 1988, intelligence data was received in Washington that, despite the Biological Weapons Convention signed in 1972, the USSR was producing the anthrax agent Anthrax-836.

Photo: social networks

From Sverdlovsk with illness

It is known that Anthrax-836 was produced in the military biological laboratory of the military town of Sverdlovsk-19, located in the Chkalovsky district of today’s Yekaterinburg. On March 30, 1979, an outbreak of anthrax occurred here . The accidental release of spores of the infection from the military laboratory into the atmosphere occurred due to the negligence of the staff: one of the employees, having started work, did not turn on the protective mechanisms.

On April 4, 1979, residents of the Vtorchermet, Keramik and Khimmash districts in Yekaterinburg began to lose consciousness en masse, they began vomiting and coughing, and their temperatures rose to 40 degrees. The sick were picked up right off the street and taken to hospitals.

Doctors who had never dealt with anthrax before tried in vain to find out the cause of the epidemic. People died of “toxic pneumonia” with “strange pulmonary hemorrhage.” Two or three minutes before death, a patient infected with combat anthrax remained calm, as if he felt nothing, but another moment – and the terrible end came: hemoptysis and death.

At that time, in Sverdlovsk, according to doctors, at least 100 people died (the exact number of victims is unknown: according to official data, 64 people died). Those who survived the severe infection were diagnosed with “Sepsis” and given a document to sign on non-disclosure of information about the infection for 25 years.

The Soviet authorities concealed the real cause of the tragedy, and a whole program of disinformation was developed. The post office, radio, and press were taken under control. Work was conducted with foreign intelligence. According to the official version, the emergency was caused by meat from infected cattle. To support this version, all meat brought into the city was destroyed in Sverdlovsk, and the local police caught and killed stray dogs. Posters with a picture of a cow and the words “Anthrax” were hung around the city.

The version about contaminated meat remained the official one for many years, until in 1992 Boris Yeltsin announced in an interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda that the cause of the emergency was military developments.

Aralsk-7. Photo: MASTAK / panoramio.com

In 1988, the New York Times wrote that to avoid an international scandal, the Soviet leadership needed to destroy stockpiles of banned anthrax secretly produced in Sverdlovsk, despite the USSR’s official commitment never, under any circumstances, to develop, produce, stockpile, acquire, or retain microbiological or other biological agents or toxins that are not intended for peaceful purposes.

In strict secrecy, the military loaded the anthrax pathogen (100 to 200 tons of liquid mass) into special containers and filled them with chlorine lime. Then the dangerous cargo was sent in 24 train cars from Sverdlovsk to Aralsk, from where it was delivered to Vozrozhdeniya Island, where the substance was buried in 11 burial grounds.

A former serviceman who was involved in delivering cargo to the island from the mainland at the time recalled :

“Tanks were constantly arriving, and not only that year. I remember very well that the vehicles were moving in columns, and in each column there was one vehicle that was accompanied not by soldiers, but by armed officers. Such vehicles did not reach the destination with the others, they were left somewhere along the road. Everyone noticed this, but, of course, they kept quiet. I think they were not transporting gasoline or diesel fuel this way.”

As a result of the anthrax spore burial activities, Vozrozhdeniya Island has become the largest biological weapons cemetery in the world.

When destruction and plague came

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the drying up of the Aral Sea began to complicate the work of the test site (from 1952 to 1990, the area of Vozrozhdeniya Island increased from 200 to 2000 km²): the cost of cargo delivery increased many times over, the port had to be moved to follow the drying up sea. And with the collapse of the USSR, the work of the test site became impossible altogether. In 1992, the biochemical test site on Vozrozhdeniya Island was closed. The military personnel serving there were redeployed to Russia. The biolab, documentation and equipment were taken away. What was not transported, including the deadly burial grounds, was simply abandoned on the island.

In the following years, the equipment left at the testing ground, some elements of its infrastructure, and the residential buildings of the military town were the prey of the “black metalworkers”. Aralsk-7 was plundered and turned into a ghost town.

Aralsk resident Akhmet (name changed) visited Vozrozhdeniya Island in 1992, immediately after the military personnel, the training ground staff and their families were redeployed to the mainland. In a conversation with a Kedr correspondent, he reported that the abandoned island left a terrible impression:

— I saw two- and three-story houses. Perfect asphalt on the only street. A kindergarten, an elementary school, small grocery stores. The windows in the houses were open. Curtains, chandeliers, furniture were visible from the street. No one inside. Not a soul on the street. Not a person, not a single cat or dog. A terrible picture. People are used to seeing life in cities, and there is no one there.

The main building of the site In the now abandoned PNIL-52 (field research laboratory) for testing biological weapons. Still from ZweZet videos

In 1992, doctors began reporting outbreaks of plague in Central Asian countries, including the Aral Sea region: with the drying up of the sea, the Aral Sea basin turned into a salty lowland, which made it easier for infections to spread from the island.

The staff of the Scientific Research Center for Quarantine and Zoonotic Infections in Almaty feared that the problem would worsen—that as the Aral Sea continued to regress, the number of infected rodents migrating from the island to the mainland would increase, and their contact with humans would lead to local epidemics.

In 1995, three years after the site was closed, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan invited American military bacteriologists to Vozrozhdeniya Island to take samples from burial sites containing the anthrax pathogen and to study the contaminated area.

American trace

In the 1990s, the United States studied Soviet facilities that developed and tested biological and chemical weapons in Uzbekistan. One of these centers was the site of the Novichok nerve agent , which became widely known after the poisoning of the Skripals and Alexei Navalny in 2018 and 2020. Military expert Igor Nikulin said that in 1992, the Americans participated in the liquidation of the institution that developed Novichok.

At that time, the US was mainly working on sites in Uzbekistan – all of them were previously classified, the Americans showed the greatest interest in Vozrozhdeniya Island. However, among the sites studied by the US was also the military testing ground “Eighth Station of Chemical Defense”, located on the Ustyurt Plateau. There, Soviet scientists tested biological and chemical weapons and means of protection against them in the 1980s and 1990s. In addition, several underground nuclear explosions were carried out on the plateau during the Soviet years: three of them were in the Mangystau Region of Kazakhstan in the area of the Mangyshlak Peninsula.

In 1995, American specialists collected soil samples on the Kazakh part of the island and isolated anthrax spores. It is known that anthrax spores live in the ground for hundreds of years.

For example, a pasture contaminated with urine and feces from sick animals can retain and spread the infection for more than 50 years .

As a result of the study of the island’s pollution, it was found that the anthrax spores, despite the island’s sandy soil, which can heat up to 60°C in the summer, which is unfavorable for bacteria and viruses, did not completely die.

In 2002, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Pentagon representatives visited Vozrozhdeniya Island again. Employees of the Center for Quarantine and Particularly Dangerous Infections of the Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan, together with US specialists, carried out work to decontaminate burial grounds with biopathogens.

The exact location of the anthrax burial sites on Vozrozhdeniya Island has never been disclosed, but finding them was not a problem — the pits were so large that they were clearly visible on satellite images from space. The deadly storage facilities were defused in a joint US-Uzbek project by placing anthrax spores in a chlorine solution.

The US Congress allocated $6 million for the Vozrozhdeniya Island decontamination project .

Kazakh SSR. June 1, 1987. The graveyard of ships of the Aral fishing flotilla in the sands of Karakum. Photo: Boris Yusupov / TASS Photo Chronicle

Some experts believe that in reality the American program was of a military-intelligence nature, and not of a humanitarian-ecological nature, as was stated.

An Uzbek ecologist, who wished to remain anonymous, told the media that he did not know what exactly the Americans were doing, but noted that they could have been collecting samples of substances tested at the site.

The Uzbek-US project has raised concerns in Russia. Russia’s suspicions about the possible intelligence nature of the US program on Vozrozhdeniya Island were heightened by the fact that Kazakh authorities were not included in the cleanup project on the island, although its northern part – 70 of the 200 square kilometers – belongs to Kazakhstan.

Post-effect

Thirty-one years after the closure of the test site, Vozrozhdeniya Island remains uninhabited. According to official data, not a single person lives there, and the abandoned residential buildings of the military town and laboratory buildings continue to deteriorate (when visiting the island, journalist and geographer Nick Middleton from Oxford University noted that the buildings of the dangerous laboratories “have not been cleaned at all”, “they were simply abandoned”). And, despite the successful project of the Kazakh government to restore the Small Aral, the territory of the former island is still surrounded by desert.

However, according to Uzbek ecologists, during the island’s isolation, “amazing landscapes” and “unique complexes of flora and fauna” have formed here, “which are not found anywhere else in Uzbekistan.” However, in 2016, scientists noted a decrease in the saiga population due to illegal hunting by poachers. At the same time, no mass deaths of animals or signs of poaching were found on the Kazakh part of the island. On the contrary, researchers noted the presence of a large number of hares, foxes, wild boars, corsacs, rodents, falcons, kites, and even flamingos , and other animals.

Foreign experts believe that most of the island is no longer contaminated – anthrax spores can remain on Vozrozhdeniya Island only in the soil in small areas (their possible concentration is unknown). However, according to the results of studies in 2003-2005, the Ministry of Health of Kazakhstan isolated “cultures of various pathogens” in the northern part of the island. In 2018, 15 years after that expedition, the Kazakh authorities again noted that, despite the end of testing on the island more than 25 years ago, “certain risks remain in this territory.”

The main building of the site In the now abandoned PNIL-52 (field research laboratory) for testing biological weapons. Still from ZweZet videos

The conclusions made by Kazakh scientists based on the results of those expeditions, however, did not coincide with the conclusions of their Uzbek colleagues. Already in 2002, according to Gapar Asenov, then head of the zooparasitology laboratory of the Karakalpak anti-plague station, the Uzbek part of Vozrozhdeniya Island was safe for free visits. His colleague, head of the epidemiological department of the station, Makset Baimuratov, who, together with American scientists, studied the island to deactivate abandoned biopathogens, shared the same opinion. He said that the results of soil and water samples taken by his team on the island, as well as observations of plants and animals, showed that there was no danger: biological weapons had been successfully buried several times and no longer posed a threat to the lives of animals and residents of the Aral Sea region. Sixteen years later, in 2018, Gapar Asenov again confirmed that the results of tests taken on the island in 2017 were negative : no strains of brucellosis, plague or anthrax were detected.

Today, neither Kazakhstan nor Uzbekistan conducts permanent monitoring of Vozrozhdeniya Island. In the 2000s, many experts believed that the postponement of research work was due to the problem of delimitation of the border on the island between the two countries. However, both countries stated that there were no disagreements on this issue.

In 2018, the then Chairman of the Public Health Protection Committee of the Ministry of Health of Kazakhstan, Zhandarbek Bekshin, explained the long-term lack of constant monitoring of the island’s pollution level by the fact that no one had lived there for more than 25 years since the test site was closed. Bekshin said that during this time, not a single case of infection had been registered in the Aral Sea region, despite regular visits to the island by metalworkers. Therefore, Vozrozhdeniya Island is safe and suitable for private development – primarily for the extraction of minerals, “but with the supervision of the sanitary and epidemiological service.”

Despite this, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan still do not recommend visiting the island. To prevent unauthorized entry of stalkers and metalheads, a border checkpoint operates here.

Aralsk-7. Photo: MASTAK / panoramio.com

“We have no information”

Today, there is no information in open sources about the ecological and epidemiological state of Vozrozhdeniya Island and the results of its surveys. According to Kazakh biologist Sergei Pole, who worked on an expedition to the island in 2003, all materials from the epizootological survey of the island were marked “For official use only.” Pole believes that the results of other studies ever conducted on the island probably also remain closed.

The editorial boards of Kedr and Free Space tried to clarify the situation. The head of the Aral anti-plague station, Svetlana Isaeva, told us that

since 2021, has no right to disclose information about the ecological and epidemiological state of Vozrozhdeniya Island, and advised to contact the competent authorities.

We contacted: sent requests for information on the ecological and epidemiological state of Vozrozhdeniya Island and the results of surveys of its territory to the Departments of Ecology and Sanitary and Epidemiological Control of the Kyzylorda Region (Kazakhstan), the Department of Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, the Ministries of Health of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and the National Scientific Center for Particularly Dangerous Infections of the Ministry of Health of Kazakhstan.

The Department of Ecology of the Kyzylorda Region told us that the requested information was not available. Employees of the Department of Sanitary and Epidemiological Control of the Kyzylorda Region responded that the issue was not within their competence and advised us to contact the Ministry of Health of Kazakhstan. The National Scientific Center for Particularly Dangerous Infections of Kazakhstan also did not provide answers.

At the time of publication of the material, no responses were received from the Ministries of Health of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and the Department of Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health of the Republic of Karakalpakstan.

The secret island of Rebirth continues to keep its terrible secrets.

* Oceanographers claim that over the last thousand years, the Aral Sea has dried up and filled up again eight times. Since the 1960s, the last, ninth process of regression of the reservoir has been taking place, presumably.

https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2022/09/12/ostrov-zarazheniia-media?sfnsn=wa